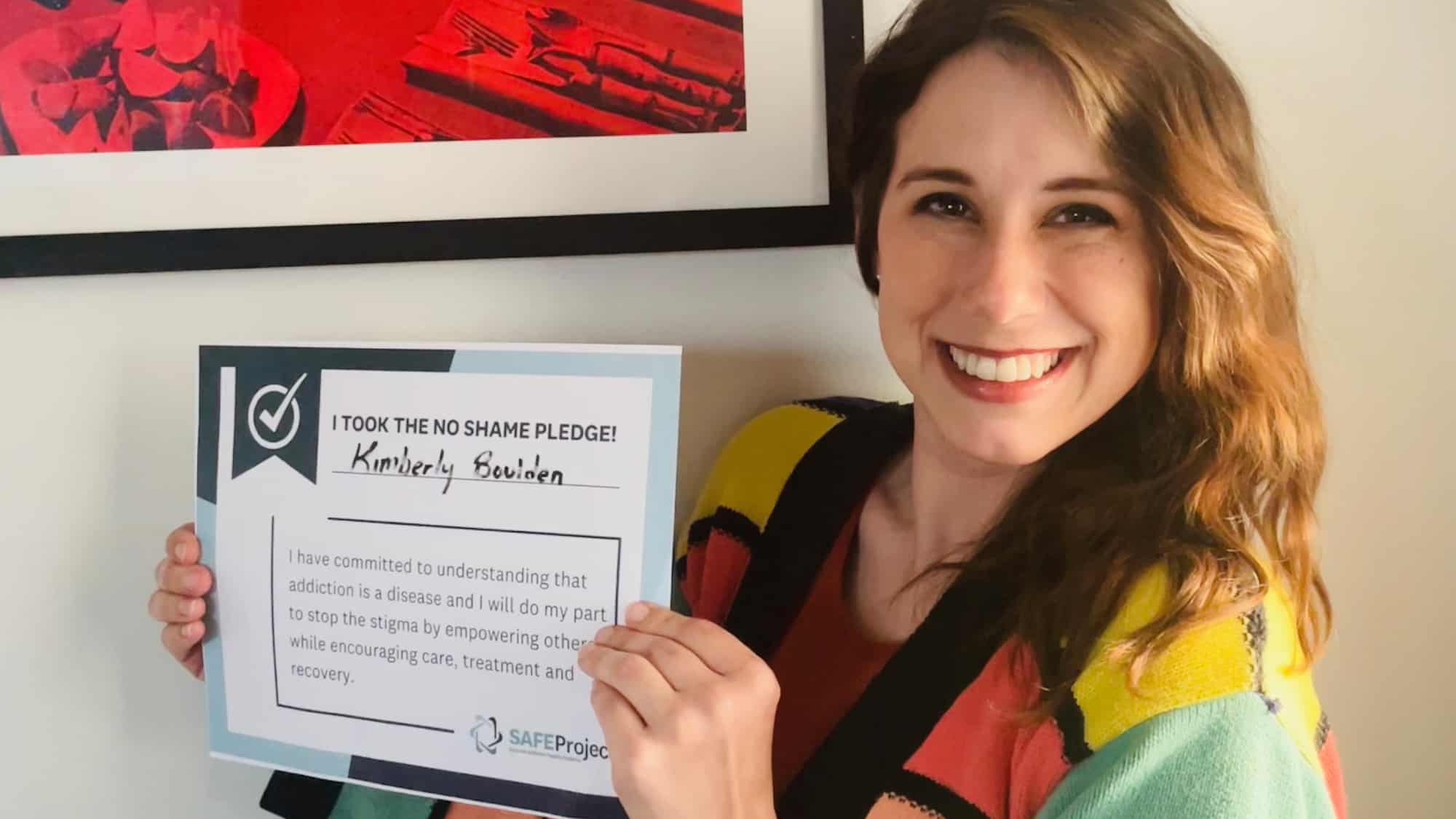

In celebration of Women’s History Month this March, SAFE Project is sharing interviews with women making a difference in the fields of mental health, substance use, recovery, & fighting the stigma that accompanies it.

Tell us a little bit about yourself.

I’m Kimberly Boulden. I am the Senior Director of SAFE Campuses here at SAFE Project. My team and I look to promote recovery resources, as well as destigmatize substance use on college campuses across the country.

Why is this work important to you?

I think if you would have asked me two and a half years ago why I came into this work, I would have told you it’s because I have family members who have been impacted by substance use disorder and have found recovery through a variety of pathways.

But for the past month, I have also been on my own wellness journey using the principles of Moderation Management. Like everyone, my lived experiences and pathway to wellness are personal and unique. And so I would hesitate to use the language of recovery to describe my own journey, but I will say, however, that I have been empowered to start on this journey because of the community and knowledge I’ve gained working with students and with SAFE Project. Together, we’ve done a lot to de-stigmatize this work and that has challenged me to rethink what ‘healthy’ can look like.

Why do you think your work is important for college campuses, college students, and collegiate recovery in general?

In the past 60-ish years, campuses have been on a journey of questioning how institutions were built and for whom they were built, and in turn trying to evolve to become more inclusive spaces. In the 60s, we saw (and continue to see) this movement towards Black student liberation with the incorporation of Black student unions. We saw professional organizations like law and medicine opened up to women. We’ve seen movements for LGBTQ student rights on campus. And somehow recovery and support for people who have a relationship with substance use has not been as loud nor is it proudly talked about as part of these conversations about equity and access to college campuses.

What I love about this work is that it can be really challenging to step in, especially if you’re part of a campus community that wants to do the right thing, but you don’t know where to start. And you’re not even sure who the students you’d be benefiting are. You want to meet folks where they are. But where are those folks? I feel like our team helps create that roadmap, helps create those brave spaces just to start the conversation with students, their peers, administrators, etc… which, to be honest, we as a society have avoided these conversations because of stigma and shame. So it is thorny and complicated work. But, I hear on a weekly basis from students about how this work is positively impacting their lives. And so every time there’s red tape, or a barrier or an obstacle that feels like “two steps forward, one step back,” we are reminded by the people we are walking alongside that this is really meaningful work.

How did you see all of this play out while you were going through school? Is that part of the reason why you’re fighting so hard for this?

I’m dating myself a bit here, but I remember when I was looking at colleges, there were lists like “Top 10 Party Schools in New York State” or “Top 10 Party Schools Nationwide,” and these lists carried a lot of weight in college searches. I am ashamed to say that I was accepted into the Honors dorms, my freshman year of college, and I opted not to live in the Honors dorms, because I thought that there wouldn’t be any parties there. I remember that the transition from high school to college — not so much the academics but the independence — was really difficult. I also remember reaching out to friends for substances to help me focus and to help me meet deadlines… I can easily see from my own experience, how substance use is not even just normalized for young people, in some ways, it’s glorified. And now, as someone who has spent a long time in school, I’m seeing that it doesn’t necessarily have to be that way.

With your experience or the experience of the students you’re currently working with, if you add recovery to the equation, maybe substance use disorder or some anxiety or depression… Talk about things being difficult to manage!

I’m really blown away with the students we work with and how much they’re managing. We have students who are parents or who are interns and managing triple majors. I feel like there are more expectations and pressure than ever before on young people to stand out and make a name for themselves — to hustle. And you would think that that pressure would have us looking at our students in this way of, “Oh my gosh, what do you need? How can I help?”

So how does all of that play into why you do this work?

You know, I see myself throughout my studies, and hopefully my career, as somebody fighting for space within systems where folks weren’t necessarily thought of, or welcomed historically: I got a degree in Caribbean Studies; worked at a nonprofit for victims of domestic violence; I got a PhD and wrote my dissertation on the ways higher education leaves Black students out of experiential learning opportunities. And so through all of this work, I’ve seen that our systems are built by and for some people, and others feel like they get left behind or feel like it’s on them to work twice as hard to fit in.

Because of stigma, and because of this idea that people who use drugs or people who are in recovery are somehow lesser than or to blame for their own life circumstances, that’s inhibited our opportunity or our ability as a nation to really engage with this community in a way that matters, or in a way that’s meaningful. We’ve historically taken this “Us” and “Them” approach when thinking about people in recovery and people who use drugs. They’re those people in that part of town, when the reality of my life is that those people are an uncle, a sibling, a dear friend. They’re the folks that I work with every day. The more we normalize that conversation, the more we’ll be able to step into this broader conversation. It’s not an “us vs. them.” It’s all of us.

There are these moments where you realize, okay, we’re moving the needle here. And so the direction shouldn’t be like, “Mission accomplished; we’re done.” Instead, let’s push a little harder. Let’s try to go a little farther.

What is one piece of advice that you would give a student out there that’s in recovery, or a student with a disability, a student struggling through just everyday stuff, or someone that just is being marginalized?

There is a lot of value in being authentically you. There is also a lot of value in trying to find the ways to harness your lived experience, your expertise, the things that you do really well. So, lead with those strengths.

I think that, particularly today with the internet, social media, and access to all of these stories and all of these images every day, we end up comparing ourselves and holding ourselves accountable to these ideals that maybe aren’t really grounded in real life. Rather than thinking about all the things that you don’t have, I would challenge you to think about all the wonderful qualities that make you who you are that only you can bring to the table. Look at yourself from a position of strength, rather than from a position of deficits.

I hope that as women, as allies, and as supporters we're in this movement where we're challenging and asking for more inclusion and acceptance when we answer, 'who gets to write the rules,' because I'm tired of living by rules that other people wrote for me.”

So this is not only showcasing the work you do, but also it’s Women’s History Month. As a woman, why do you think it’s important to do things like this: showcasing women out there that are doing the hard work in this space to turn the tide?

Maybe this answers your question, maybe it doesn’t. But while you were speaking, I was thinking about when I was pregnant, the list of things that I couldn’t do. Like, I couldn’t have more than so many milligrams of caffeine, I couldn’t have unpasteurized dairy, I shouldn’t have brie, and sushi was out of the question. There were just these exhaustive lists of all the things that we shouldn’t do. And yes, I understand where these concerns come from, but at the end of the day, the abundance of rules and regulations aimed at women underscores that as a society, we continue to police women’s actions and bodies.

And when I zoom out, I feel like those lists of things you shouldn’t do translates every day into the way that we as women live, and operate in a patriarchal society. There’s all of these “shoulds.” And what I love about this work, and being a woman in this work, is that we’re questioning those “shoulds.” Like, what should a student look like? What should a professional look like? What should a woman do in terms of a career? What makes sense for a mother? I feel that there’s this wonderful intersectionality in all of this work, where we’re just challenging those “shoulds.” You get to define what a woman should do. You get to define and choose what works and makes sense for your life based on your objectives and goals for happiness. And we can throw those “shoulds” out the window.

Everything is subjective through a human lens. And so who gets to write the rules? I hope that as women, as allies, and as supporters we’re in this movement where we’re challenging and asking for more inclusion and acceptance when we answer, “who gets to write the rules,” because I’m tired of living by rules that other people wrote for me.

YES! Okay, so how should that idea of “who gets to write the rules” play into Collegiate Recovery?

I am a strong supporter of the idea of, “Nothing about us without us.” It should be those most impacted by these systems that are there helping to build and create new systems. I want the folks that can lead the charge to step into those leadership roles.

In this field, we will find new ways of doing things. And then we will find the ways that that new approach has left some folks on the margin. It’s really about this commitment to the journey to radical inclusion for everyone, which is a goal that I am committed to. It’s not a single goal, but one I feel will continue to evolve — as one new door opens, you see seven doors after that.