Dustin Huckabe is a member of the inaugural SAFE Project Leadership Academy. While a social work senior at the University of Oklahoma and president of OU’S Students in Recovery, Dustin worked tirelessly to advocate for the creation of a campus recovery community at the University of Oklahoma as part of his IMPACT Project for Leadership Academy. He is one of two students chosen nationwide as this year’s Collegiate Recovery Student of the Year by the Association of Recovery in Higher Education.

Congratulations on your award! What does this mean to you?

I hope this award helps bring national awareness to collegiate recovery and the efforts of the University of Oklahoma (OU) students who are creating a safe, sober environment for our peers. In the rooms of recovery, we receive a chip to signify lengths of sobriety and if you have been around long enough you come to realize that receiving a chip isn’t about you—it’s for the new comer to see that recovery works. I view this award the same way, it is a huge personal honor, but more importantly I think this award can help university administrators realize the importance and validity of a collegiate recovery community.

Tell us about your own journey in recovery and how you came to be at OU?

My journey with recovery and the life changing impact it had on my life starts like many others. The underdog, the kid who couldn’t pass the first grade and didn’t learn to read until the 5th grade. The kid who got in constant trouble in school and was deemed useless by my teachers and peers, in short, the class clown.

I tried getting sober at the age of 18, because my parents and my lawyer said it would look good in court. Needless to say, I was living up to the low set bar that was placed in front of me.

My collegiate journey began years before my sobriety began. I first enrolled in community college courses prior to my sobriety date, but failed due to my inability to stay sober. I finally sobered up at 23 years old on May 26, 2011. My recovery journey has changed over the course of these past eight years—I have learned so much about myself but more importantly I have learned how to show up in my relationships with my family and friends.

When I was about two years sober, I enrolled in a night class at San Antonio College, to see if I could successfully complete a class. My girlfriend Emma, who is now my wife, transferred to Texas Tech University so I transferred to the local community college in Lubbock. We met members of the collegiate recovery community at Texas Tech, who told us about the community and the potential scholarship opportunities available to students in recovery.

I applied to transfer to Texas Tech and the Center for Collegiate Recovery Communities at Texas Tech. Although I was denied acceptance by the university, I was accepted by the Center which allowed me to become a student of both. Suddenly, I was thrown into massive lecture halls, ample amounts of homework, and a robust on-campus recovery community.

Emma graduated from Texas Tech in May of 2018, and we moved to Oklahoma as she started her career. I transferred to the University of Oklahoma (OU) but quickly felt isolated and alone.

What is it like to be a college student in recovery?

College is incredibly intimidating and stressful. Being surrounded by a culture that promotes drinking is difficult, especially when you are advocating for recovery—you feel alienated from your peers when you get laughed at or are given strange looks.

There is a stark contrast between Texas Tech University and the University of Oklahoma when discussing what it’s like to be a college student in recovery. At Texas Tech, I never felt like I was a “marginalized student” and never felt alienated from my peers because I was constantly surrounded by a community of peers in recovery by being a member of The Center for Collegiate Recovery Communities at Texas Tech. As a member of The Center, I participated in various community service opportunities through their student organization, made life-long friendships, and was able to have the college experience that I never thought I would have.

At OU, I feel unsupported, unheard, and that addiction and recovery is still very stigmatized on campus. This made me realize the importance of a collegiate recovery program (CRP) because of the positive impact it can have on a recovering student’s college experience.

What led you to create a recovery organization at OU?

I felt isolated on campus especially after coming from such a robust recovery community at Texas Tech. I was so used to being able to go and hangout at the center and talk with people who were just like me.

I reached out to Vincent Sanchez, the Associate Director of the Center at Texas Tech and he told me to create the space I needed, so the journey started. I started a weekly, all-recovery meeting, a student organization, joined the SAFE Project & ARHE Leadership Academy, and began meeting with university administration to make them aware of CRPs and their potential impact on recovering students’ collegiate experiences.

What do you think it will take to normalize recovery on campuses?

When I created our student organization “United Students in Service”, I assumed the name would help students in or seeking recovery feel safe if they wanted to join. Once more students joined the organization, they wanted to change the name so that we could be bold in our pursuit of normalizing recovery on campus.

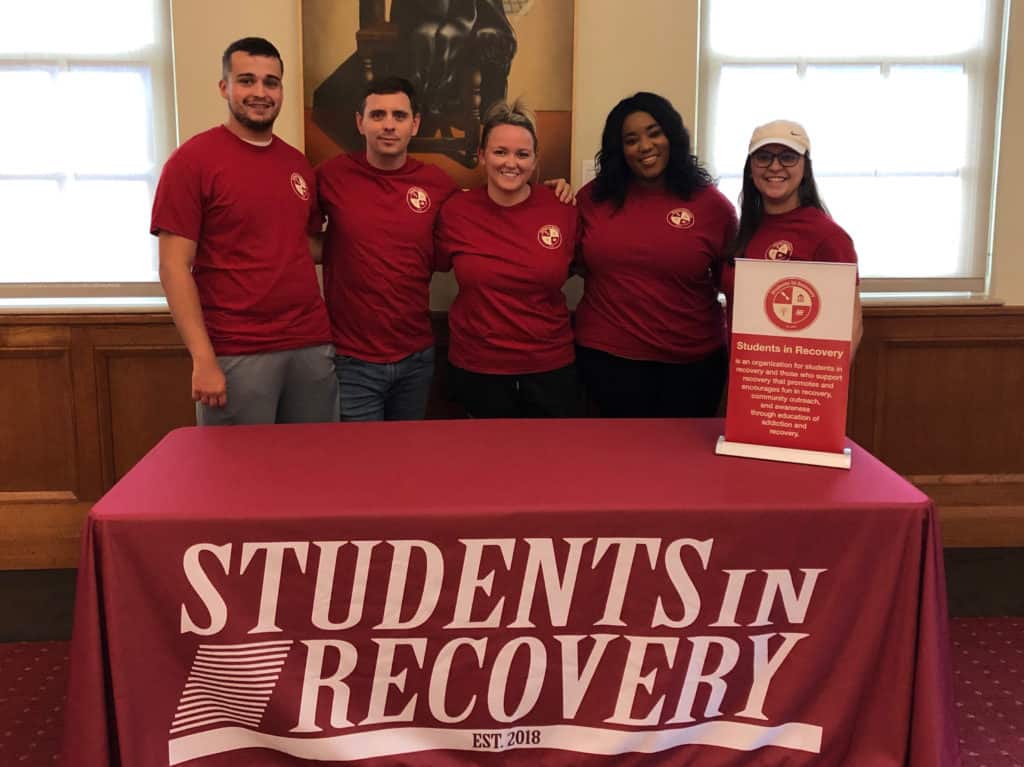

We changed the name to Students in Recovery (SIR) and had T-shirts made that say “Students in Recovery” on the back. We participate in many campus events and hand out flyers on-campus to promote our organization. SIR is a mixture of recovery advocates and students in recovery, and all want to expose the university community to recovery by putting our organization out there. It’s empowering when you have a group of students that are all wearing recovery T-shirts, walking around campus, being proud of who they are and the work they are doing to destigmatize addiction and recovery.

What inspired your Impact Project at OU for the SAFE Leadership Academy?

In 2017, I went to ARHE’s national conference in Washington, DC and was blown away. I did not realize how many people were advocating for CRPs and how passionate they all are.

I remember sitting in the town hall meeting and thought, “This is what I want to do. This is how I could be of maximum service to those around me”. I never had the intention to create a collegiate recovery program anywhere. I just knew in my heart this is where I want to end up, working within a CRP doing anything to help.

Transferring to OU gave me the opportunity to try and do just that, be of service through advocating for the implementation of an OU collegiate recovery community. I know that having recovery meetings on campus and the work the student organization has done over the course of this year has been incredibly impactful not just on campus but also within the Norman, OK community.

What challenges did you face while trying to create this new program?

One of the biggest challenges is the university has been reactive versus proactive regarding social issues. Recovery and addiction can have negative connotations associated with them, especially for those who don’t know what recovery is or looks like. Due to this stigma, it is difficult for OU to admit there are students on campus who suffer from addiction.

The second biggest challenge is the stigma that surrounds students in recovery because they are associated with the word “addiction.” At some level, the university believes they would be supporting students who are “bad” and have the potential to cause harm. However, there is a big difference between a person in active addiction and one who is in or seeking recovery—our goal is to support students in recovery, not their addiction.

Third, OU has had two presidents in the short time I have been there, since the Fall of 2018. This instability may have caused uncertainty for the faculty and staff, as well as limiting their ability to develop and implement projects.

Lastly, lack of funding is a big issue. However, I worked with the development office and found numerous family foundations and national grants that support the development of CRPs. I have also met with several private donors who want to donate to help implement the program, but without an OU collegiate recovery program there isn’t a program for them to donate towards.

What’s next?

Throughout this process, I have shown administrators the data that has been collected over the years on CRPs—that the retention rates, graduation rates and average GPAs of collegiate recovery program students on average surpass those of the entire student body. Although there is adequate research on student’s success in CRPs, there has been push back from university administrators because research hasn’t been completed for the University of Oklahoma regarding students in recovery or those with a substance abuse disorder.

To fulfill this need, I have joined the Knee Center for Strong Families to conduct research at OU to provide exact data on how many students we have on campus that are in recovery or are seeking recovery, and how many students could benefit from a collegiate recovery program. The ability to provide OU’s story with clear data will hopefully help administration recognize the need for a CRP on campus, although I do not think that data specific to the University of Oklahoma is a requirement to show the validity or necessity of a collegiate recovery program.

You were part of the SAFE Project’s first Leadership Academy Class in 2018. What has that been like?

I have learned so much about myself over this past year—I grew in my own recovery emotionally, physically and spiritually and developed skills that I never knew or thought I had. Every time I met with university administrators, I would shake because I was aware of the impact that a collegiate recovery program can have on someone’s life and I didn’t want to mess that up. The most rewarding times are during our Wednesday night, all-recovery meetings.

Currently, we have at least eight attendees at each meeting and I have seen at least six or seven students come-and-go from our meeting during this past year. This past spring semester, we had one student attend our meeting because he had heard about our meeting when we first started it in the Fall of 2018. To know that he found our group and support on campus meant everything to me.

Sometimes, I get caught-up in how political and daunting it can be when speaking with administrators but am reminded of the real reason we are doing this whenever a student seeking support in recovery finds our group or meeting. I smile every time this happens because I know that the work the student organization and the meetings are doing, reminds me that it’s working—it is just going to take some time.

What advice would you give to other students about how to convince their own universities or colleges that recovery communities are worth the investment?

Be realistic in your pursuit—think small in terms of what can you do right now that doesn’t cost much money. Start a recovery meeting on campus, having the meeting format be an open discussion meeting about recovery related topics so that if someone who has never been in a meeting doesn’t feel pressured to speak. Start a student organization, speak with your student government association, and get involved within the community.

Reach out to local treatment centers, halfway houses, or sober high schools if your community has one—being able to get community buy-in has been incredibly beneficial for us and presenting data has been very helpful in terms of keeping the conversation going.

Develop a plan-of-action, know how you are going to get to Point A to Point B and paint the picture for the university administrators or community activists, so that when they ask questions you know how to answer their questions. Assume that the administrators or community members don’t have any knowledge of collegiate recovery communities, so that you leave no stone unturned. Reach out to the university development office and ask them how they develop new programs and where funding comes from.

The beautiful thing is, is that CRPs and communities have been around since the 1980s and you are not reinventing the wheel—they have a proven track record for being successful, depending on the university’s investment. You may be introducing an unheard-of idea, but you are not inventing something that hasn’t already been successfully implemented. To reemphasize the national relevance of CRPs show comparable universities that have a CRP. For example,for a Big 12 schools, show them schools within that same conference that have a collegiate recovery program.

In summation: create the space, empower students, and keep being persistent. Your standards should be high, because the stakes are even higher, remind them that you are talking about students’ lives.

What do you tell others about the benefits of CRPs?

The lifelong friends my wife and I have because of the CRC at Texas Tech are invaluable. The fact they gave me a space to be who I am and not have to wear a mask to hide who I am is invaluable. The time, energy and support from the staff is something I can never repay. CRPs not only offer students who are in them an amazing opportunity, they also contribute positively to the university as a whole.