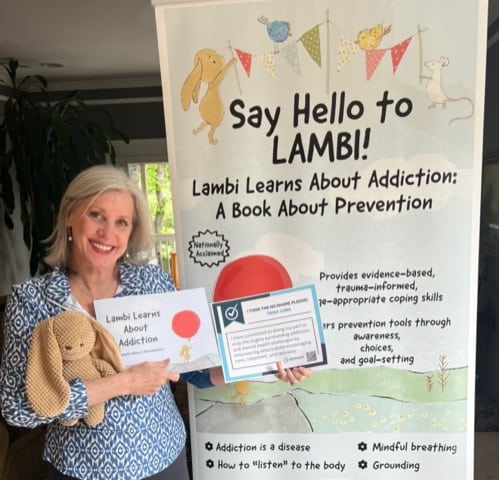

In conjunction with Mental Health Awareness Month this May, SAFE Project interviews Trish Luna, author of Lambi Learns About Addiction: A Book About Prevention:

Trish was kind enough to sit down with SAFE Project to discuss Lambi’s story, as well as share advice for parents on how to broach the subjects of addiction with very young children.

Can you introduce us to Lambi?

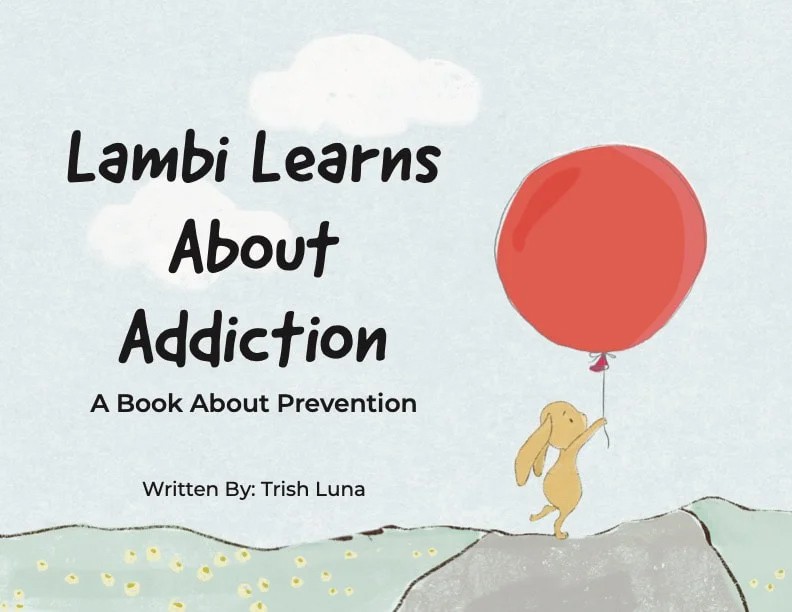

Lambi came from a space of knowing that I needed to deepen and broaden this conversation. I had been approached by some state organizations asking me to develop a character, and I just sort of sat with that idea. People who are songwriters say, “oh, this line just came to me,” and this literally just came to me: “My name is Lambi… but I am a bunny. Isn’t that strange and isn’t that funny?”

There’s a lot of history. My daughter is Samantha, and her nickname growing up was “Sami Lamb,” which then became “Lamby.” That wasn’t a driver or the original intent of that, but it felt like there was a deeper meaning there. When she was a little girl, her favorite lovey was a bunny. So maybe that was in my head somewhere all these years, but there it was: “My name is Lambi… but I am a bunny. Isn’t that strange and isn’t that funny?” Right away in the first line, what happens is things get turned on their head, right? Things aren’t as they appear.

So often that is what is going on with addiction, and in families’ lives where so many things are happening that aren’t what they appear. That doesn’t necessarily have to be a negative thing, but it can also be a mechanism that’s in place to hold people in silence due to the stigma or the shame.

“My name is Lambi… but I am a bunny.” There are some personal identification questions surfacing through the character within the first line.

Absolutely. I was working with a team in West Virginia about doing an evidence-based study, we were talking about Lambi, and I was sharing the initial parts of the story. Someone on that team said, “I love that because there are a lot of people who question their identity.” I can’t claim that I was trying to do that, but as soon as it came out, there it was. You just feel that validation, that this is an important thing to say. We’re saying a lot right in those first two sentences, creating a safe space for a difficult conversation.

There is some striking imagery with the parent in the closet with the wine bottle, and we see some pills spilled on the floor… but then you flip the page and you see this balloon floating away, and it’s this relaxing, literally letting go of things visual representation. How conscious were you of setting those against each other in the book?

Extremely. I’m so excited to tell you about the illustrations. These come from one of my dearest friends, Kellie Montana, who is a professional and a commercial artist. When I was switching to this project, she said to me, “I would love to work on this with you. I’ve never done illustration before, but I would love to do this.” This woman is the most precious, dear human and has such an eye and soul for people. She just sees people. We sat down and the beautiful thing is we did this book in three weeks because I had a deadline to get it to the publisher before they shut down to print yearbooks. I asked if we thought we could do this in three weeks, and she said that was a piece of cake; her deadlines are normally two weeks! She had never done this before, but we sat down and storyboarded with the words, and we sort of laid out what the images would look like.

It was a challenge at first to get the character fully drawn. It’s an interesting process to see. She would draw something, send it, I would then send that out to a test group and get feedback. She would say, “off by a little is off by a lot”… and she just went back to work on honing it in.

This story originally came from me wanting to write something for my children around thirty years ago about their father’s addiction. I always wrote it from the perspective of the father being the subject that was having the substance use disorder problem, but my granddaughters… it’s their mother, my daughter, who struggles with addiction — they have not seen her for two and a half years; my daughter really struggles with this disease…

When my granddaughter was reading this book, this page in particular is where the words were talking about a “daddy” having this problem. She looked over at me and she said, “Lulu, the next book that you write should really be about a mommy.” I asked if that would be OK with her, and she said yes, that it was really important. She’s eleven. I thought, how brave of you to be able to want to talk about that.

This image was a scene that basically happened with my granddaughters, with their mother. She had gone into the closet, and one of them is more curious, so they saw things that are very hard to see. That was the reason this was drawn. But again, it was originally depicting a father, so I went to Kellie and said, okay, prepare to have your heart ripped out at the root. She said no problem, and within twenty minutes, she had redrawn this. I just reworked the words to make it about a mommy. So it’s very purposeful.

As for the next page, interestingly, Kellie had just sent this image of Lambi with the balloon. It did something to me when I saw that. I started thinking about how feelings get so big, like a giant balloon. This was just such a collaboration of ideas and expression, because the words say one thing, and the images take it so much further.

"My name is Lambi… but I am a bunny. Isn't that strange and isn't that funny?" Right away in the first line, what happens is things get turned on in their head, right? Things aren't as they appear. So often that is what is going on with addiction, and in families' lives where so many things are happening that aren't what they appear. That doesn't necessarily have to be a negative thing, but it can also be a mechanism that's in place to hold people in silence due to the stigma or the shame.Trish Luna

In addition to Lambi, we have the other animals, and sometimes they’ll have their own little dialogue bubbles. Can you tell us about the other cast of characters?

Kellie has always had animal characters in her art that she has done over the years. She was able to quickly create this whole community around Lambi. The little mouse we’ve named Owen. That’s my youngest grandson. She would just add these little pieces saying, “you are brave,” and how important is that to hear? In that scene, Lambi says they also imagine holding their heart. “I hold it so close so it won’t break apart.” That’s anchoring. That’s something that we all can learn from to feel better.

Jerry Moe is the retired director of family programs at Betty Ford Hazelton and the author of many, many very successful books. I asked Jerry to read this and give his feedback. He actually wrote the introduction for the book. He said that he loved the story, but wondered if there wasn’t a way that you could also be showing a dad. If you can see yourself in the story or see your situation in the story, there is a deeper connection. The other animal characters were just kind of standing there, and so Kellie changed the expression on the meerkat standing on the couch to show his dad in rough shape. There’s a lot jammed onto each of these pages with a lot of intention and meaning.

From an authorship perspective, how easy or difficult was it to come back to this writing style and find new things to say in new ways?

If somebody asked how long it took you to paint that beautiful painting, you could say couple of hours, but you’ve been working on it your whole life, right? The blessing and gift is this rhythm is in my head from reading in this style so often. It is something that I felt drawn to. With lots of practice, it became easier. To be able to write in short sentences and get across very important statements, that became easier as well. Even when we had to pivot and make the story about a mommy being the character, I’m very lucky that it comes naturally from years of doing it.

You’ve shared both with the previous book and now with Lambi that it stems from your own personal experience with your family. Who is the audience for this new book?

I like to get as young as possible. The beauty of this book is you could read it to a three-year-old. There’s nothing in there that couldn’t be safely shared with very young children. They’re just hearing the words and getting coping skills. These are things that we all should be learning. One of the interesting things that I found is when I was out and with older kids — 11, 12, 13 years old — they were really starving for the kind of validation in these words.

Is there anything else you would like to share?

I have really done a lot of my own research and taken classes about the neurobiology of attachments, and the more coping skills that we can equip children with, the better outcomes we’re going to have. So originally, back when I was in my twenties and knowing that words had to be put on paper to have this conversation with kids, my main goal was just to say the words. We’re just going to speak the words about this in public and acknowledge that this was what was happening, to acknowledge what kids’ feelings were, and then discuss what they could do about it. It was not their fault, these are natural emotions to have, they’re safe to have, and then really having them be able to create their own space. The more I learn in these fields, the more excited I am about these somatic therapies.