As Samuel “Kevin” Johnson will tell you, his experience growing up was characterized by trauma and violence — when what he really needed was counseling, job training, and education. After many years of struggling with drugs and alcohol, he knew it was time to get help or lose everything that mattered to him.

This is his story.

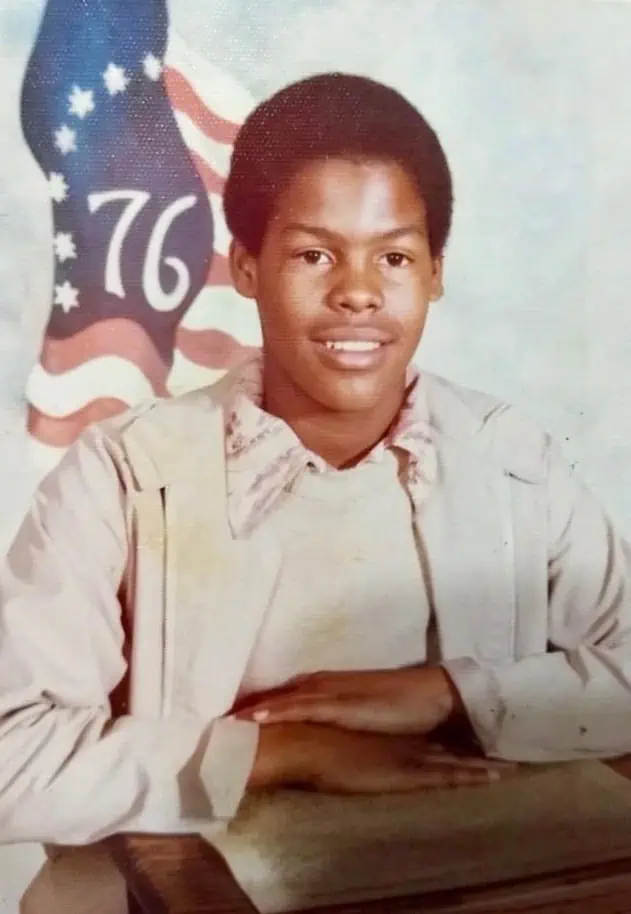

Growing Up

I grew up in Washington DC in the sixties. I remember taking karate from the Black Panthers. They used to teach us martial arts and they fed us breakfast. People used to think they were a bad organization, but they were teaching us to be Black and proud, teaching us to be who we are, and trying to empower us.

One of my earliest memories of trauma was when I was five, and Martin Luther King Jr. got killed. I remember that day — my mom came and got us out of school, and she took me to my aunt and grandfather’s house. That night the riots started.

I remember going to the corner and watching all the looting and rioting, and I remember my mother being at work. I was afraid because I saw them turning white people’s cars over, and my mom drove a white car. I was scared to death. My father worked at the liquor store at the corner, and I remember them standing in front of the liquor store with shotguns protecting the store.

At around six or seven, I moved in with my grandfather and aunt because my mother was an addict and she got locked up. She was a heroin addict and wasn’t allowed treatment back then, especially for Black folks. They would just jail you.

My mom would go in and out of prison. She would be gone for a year or two, come back out for a couple years, go in for four or five years, come back out. When she was out, we would live somewhere together. When she was in, I would live with my grandfather and my aunt.

My mom was my world. I was her mascot, everywhere she went, I went. We used to travel to Philly, New York, and down South to Ruckersville, VA where she grew up. We would go to our annual church reunion in Ruckersville, and always stopped at the 29 Truck Stop. We would always go through the back door, but up until I was 10, I never really understood why. We’d see other people going in the front door, but we’d always go through the back door.

I said, ”Mom, why are we always going through the back door and through the kitchen?” and she said, “Baby, this is just the way it’s always been. This is what we do.” I was like, “What? We are not allowed to go through the front?” And she said, “I think we are, but we’ve just always been doing this.” I was a little rebel and I raised hell. I said, “If we’re not coming in the front door, then we are not coming in here no more, Mom.”

That was the last time we went through the back door. We always went through the front door after that — she felt proud, she looked at me and smiled.

In The Streets

Growing up in southeast DC like I did, it was kind of rough over there. Drugs had become a big problem there, especially when cocaine came in the early 80s. DC became like the wild, wild west.

I didn’t want to be in the streets, but that was what I knew. It’s what my friends were doing; everyone was doing it. As a teenager, I had to support myself and did whatever I had to do to support myself. I had always worked odd jobs, I sold a little weed, a little PCP here and there.

I remember my mom, when she would be out, would be on the streets. I remember being 13, and I’d catch the bus to go to where she would hang at, look for her, and try to give her a couple of dollars so she could get her fix and a hotel room for the night. This went on until my 20’s when she would go in and out of prison. It wasn’t until the 90s that she got some help.

I needed resources like counseling, job training, and someone to help me with my education, but I never got it. I worked, did what I had to do, just trying to get by. I lived in rooming houses, efficiencies, and stayed with friends.

Back in 1980, I was in a school called Metro Studies funded by the federal CETA program. It taught trades to young Black men in the cities and I was taking up sheet metal, got a little check each week, learning this trade, and it was going to help me get my GED – but President Reagan cut that program. If I could have finished that program at sixteen? My life would have been a whole lot better by the time I was twenty, but I went back to the streets again.

My family (my grandfather and my aunt) knew I was a little street crazy. They would let me come stay with them for a month or two. They’d say if you come here, you’ve got to stop selling the drugs – no more of that gangsta stuff. You come here, you save your checks up for a couple of weeks, maybe a month, and you can get your own place again. That was the best thing my family did for me and I appreciated that because it didn’t enable me to sit back and say I’m going to be a hustler. I always had little jobs, but they didn’t last because I always went back to the streets.

But I started seeing some of my friends die. At about 18, I saw a guy I knew walk up to my best friend, and blow my friend’s brains out because he snitched on some caper they pulled, and that kind of freaked me out. After seeing my friend getting killed, my family moved to Maryland.

My behavior followed me out there. I was still back and forth with trying to sell a little weed here and there. They put me in jail out there for two months for robbery, a crime I didn’t commit. I was almost 20 – I got out and eventually charges were dropped. From there, I wasn’t quite ready yet, and I was still messing around.

I entered the Job Corps, where I met my first wife. I stayed in there a month or two but got kicked out for my behaviors. I had an apartment and was married, but I was left alone a lot when she went back and forth to Pennsylvania with her family. I would party and do drugs a lot, stuff like that.

After all that mess, I was ready to get off the streets and a few years later I was able to get a job. Finally, someone offered me a job paying $3.85 an hour working at a liquor store, and I took that job, and left the streets alone. I stayed there 16 years and bought my own store.

It taught me that I didn’t want to be like them, down in the streets. And I knew that if I kept going the route I was going, I was going to die in the streets. I always looked for a way out – I always looked for somebody to give me that break, to give me that job, to stand by me.

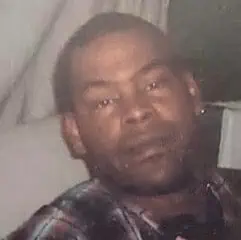

“I Didn’t Know I was Addicted”

When I was on the streets, I didn’t know I was addicted. I didn’t know I was an alcoholic. I just thought I liked to party every day. In 1989, that was when I first realized I needed treatment because I became addicted to cocaine and crack.

That’s when the streets were flooded with cocaine. I basically had a crack habit for about seven or eight months; I started using and couldn’t stop. It became an everyday thing. I had been at my job for about five years, and I told my employer that I’ve got to leave here because I’m hooked on cocaine. I basically lived on the streets for four more months. One day I just woke up on some church steps crying, and said I got to get some help.

I tried to steal something out of a local clothing store, they caught me, and they arrested me, and that was when I was first introduced to 12 Step programs and treatment. I never really knew about treatment because anytime my mom got locked up for her drug habit, she went to prison. They never offered her any kind of treatment.

My lawyer said, you’ve been working hard for 4-5 years, you’ve been staying out of trouble. She suggested, maybe you should try some AA meetings. And I’m like, I’m not an alcoholic. Now, I had been an alcoholic since I was twelve – because that was something I always thought I could handle. They told me about the other fellowship, NA, and when I thought of “narcotics,” I thought of people like my mom. Sit around and nodding, and I’m like, no, I am not really interested in that.

I did a thirteen day detox, and was introduced to 12 Step meetings. I hung around those rooms for eight years, and I managed to stay clean for seven of those eight years.

Thank God, the guy I worked for, for 16 years – it was a Jewish family. They took me under their wing, I was like their son. Even when I went into my 13 day detox, went through my drug bit for seven months, soon as I got clean, they were like, “Your job is here for you, buddy, come on back to work.”

All that taught me was that I had to work hard. Coming up, I was uneducated because I had to drop out of school to take care of myself all those years. I knew from day one, that I had to work twice as hard as the next man. And I had to just not give up, just work hard. Things were going to get better.

Finding My Recovery

I had worked all those years, managed to buy my own business, and I had married my second wife. I was working 12 hours a day, 6 days a week. When she wanted a divorce, we did that, and I sold my business. I bought another little store – I sank every penny I had in that store and I lost my tail. I was in Pigtown, Baltimore (a southwest neighborhood). Things got bad and I started drinking hard.

At this time, I met the woman who would become my wife. Brandee was going through the same thing I was going through – she was going through a divorce, facing some stuff and trying to clean up the wreckage of her past.

I guess the two things that made me stop was, one, I gave up the business so I had to get a job. Here, I had been working hard for 27 years, but I was unemployable. I could not pass a drug test. Then Brandee, she gets locked up. She went in for two months, she came out. I had already stopped smoking weed, but I was still drinking a little bit.

On May 12th in 2011, she got out and gave me this look like, we can’t do this anymore. No more partying. Basically, I knew that she was going to have to leave. If I kept drinking then she would too. So the next morning, May 13th, we went to the 12 Step program and we’ve both been clean ever since.

Recovery is not something you can do alone. It’s a lifelong process. To keep what I’ve got, I’ve got to keep giving it back. The first time, I kept focusing on “me, me, me, me.“ Instead of going into a meeting and thinking, what is this going to do for me, or this thing can’t do nothing for me…I go in there now and think, what can I do for this program and these people in here? And by doing that, that helps me.

The biggest thing is allowing people to help me, because I’ve been on my own since I was basically 12 or 13 years old. I’m like, “I can do it all myself – I don’t need y’alls help. You don’t understand what I’m going through. “

This time I’ve allowed people to help me. I’ve cried in some fellowship rooms, I cried on some women’s shoulders, I’ve walked in the rooms and talked about what I was going through, and I’ve allowed people to help me this time. And instead of medicating myself, I dug deep into service work because that’s what we do. It gave me commitments and I had to stick to them – and I got through it.

Recovery is not something you can do alone. It’s a lifelong process. To keep what I’ve got, I’ve got to keep giving it back.

Samuel “Kevin” Johnson

Recovery While Black

For most Blacks in the inner cities, or if you are not addicted to opioids, the only way to get treatment is through the jail system. You’ve got to get locked up, and then most times you can get treatment once you’re in jail. That’s one of the things that has to stop.

That’s how I got clean the first time because I didn’t have insurance, and there were days when I was out there and I wish I could have went into a treatment center somewhere. I was needing treatment but I didn’t have insurance, so thank God, I got locked up and I got into treatment through the jail system.

I got clean in Owings Mills, a predominantly white suburb of Baltimore. 95% of the meetings were white kids who had been in rehab 4 or 5 times, or older white people who had 20 or 25 years clean. So, I was not taken very well when I got there; they had to get used to me. I cried in the meeting, I screamed, I hollered, I mean, I wanted some help this time so I wasn’t going to let them run me out! I had to hold my seat!

I went in and made that my home. I made myself comfortable, because at first, they couldn’t stand me. They tried to run me out of there. And they will if you aren’t strong enough. They called me the “token Black man.” It was the area where I lived, and I didn’t want to go way across town. I said this is going to be my home, I stood fast, and I built it up. I was the coffeemaker, the speaker seeker, the treasurer, I set the meeting up for two or three years.

A lot of times for an addict, you get that window – a couple of hours, maybe 24 hours – to get into treatment or it’s back to the streets again and back to getting high. There were times that I wanted to get clean and there was nothing available to me. Nowadays, you can go to Anne Arundel county (Maryland), go to a firehouse or police station, you say I need treatment, and you go right then and there. They’ll bring a peer to come out and talk to you, and right away, you’re in treatment. The whole country needs that. Baltimore City, predominantly Black – they don’t have that.

Unfortunately, in the past couple of years, a lot of young, suburban white kids are dying in droves because of fentanyl and all this other stuff, heroin, and opioids. Black people have been dying for years in the inner cities from these same drugs. Fentanyl is “China White,” and that came through in the 70s, 80s, and 90s — and wiped a whole drove of people out. Same drug, just under a different name. When it was killing mostly Black people, there was nothing. Now it’s killing the young white kids? “Oh, we need to do something about this. It’s a crisis.”

I watched my mom go through that when I managed the liquor store and my mom was cooking for us over in the deli. I noticed that she started hanging out with her old friends again and she started using again. I did not want to see my mom go back to jail. So I took the day off, went back to her probation officer, and said, “Look, my mom is back on heroin again. Before you go put my mother back in prison, please get my mother some help.”

Luckily at this time, it was the late-90s and you had long term treatment programs available and, thank God, her probation officer helped her get into the Community Action Group, which was a one year program. Mom never used heroin again, and she never went back to prison since. She became a counselor for them, and cooked for them for a few years before she retired. She’s in a nursing home now – and I call her “my old soldier”: she takes a licking and keeps on ticking.

People talked about how George Floyd had fentanyl and meth in his system when he died. It wasn’t about how he lived, it was about how he died. He might have lived a rough life, and he probably had some problems, might have gotten help for his problems, but we can’t judge him on how he lived. It’s how he died. It was because of an overzealous person who thought he was judge, jury, and executioner.

Two of my best friends in the world are DC cops. They are retired now. They were community police, they watched out for the neighborhood; it wasn’t about trying to assert their authority on people. They were just there to protect the neighborhood and make sure everybody was safe.

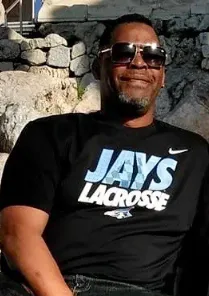

Keeping My Recovery

I persevere because of prayer, my wife, and my network of people. Whatever I’m going through now can’t be worse than what I’ve been through.

I have my own business and I’m out in the streets everyday. I’m out driving in my truck from DC, to Maryland, to Virginia. The business I’m in, I sell food, so I deal with a lot of low income people, because they have food stamps and stuff like that.

Every day, I come across a lot of addicts. I try to be a power of example. They all know I’m in recovery. I always tell them, look, I’ve got a network of people, and if you want to get into treatment today, you let me know. I got you, and I’ve done that. I’m in recovery. If you need help, here’s my number, give me a call, let me know when you are ready. I don’t judge them – I’ve been there before. Whenever you want it, it’s here for you.

This is what I have to do for me. The main thing about recovering people, if you want to keep what you’ve got, you have to give back. That’s what I didn’t do the first time – and that’s why I lost it. I’m keeping my recovery, so I’m giving back as much as I can. So I’m out there in the streets every day.

My oldest son is in the military, a staff sergeant in the Army with the 82nd Airborne. He’s in Italy now, but he’s coming home. He’s a kid that every man should have. I told him to get a career, don’t end up on the streets, go see the world, and he did that.

I’ve always told him, especially the last 15 years, “When I grow up, I want to be just like you.” But he always told me, “But Dad, I want to be like you. I just want to work hard and just take care of my kids.”

The thing I tell my kids is just persevere, work hard, and anything is possible in life. I’m a Black kid from Southeast DC. I call myself the “Other All-American Boy.” I got over my addictions, my trauma, and emotional things because I allowed people to help me, and I just keep trying to work on being a better person.

I didn’t stop getting high because I ran out of money. I stopped because I was tired of the pain I was going through. I wanted to learn how to deal with my emotions. Allow somebody to help you and help other people: the more I keep trying to help other people, the more it helps me.

I love going out there and passing out the drug disposal bags, and mingling with the community. When you are passionate about recovery, you want the whole world to be clean. That’s what keeps me going. I wish I had somebody like me when I was a kid.

Samuel “Kevin” Johnson is a Washington DC native, and has been in recovery for over a decade. A lifelong entrepreneur, he is a food wholesaler. Samuel is active in the recovery community as a sponsor and advocate.

He volunteered for SAFE Project, and proudly displays SAFE Project’s “BE SAFE” signage on his company truck. Samuel takes time with his customers to educate them on treatment, recovery and proper drug disposal using drug disposal pouches.

Share Your Story

This epidemic has given us one common experience: we have all become experts in our own way. At S.A.F.E. Project, we believe that we strengthen one another by sharing our stories. Whether you are in recovery, lost a loved one, or are making a difference in your community, you can help others on this journey. We’d like to hear from you.